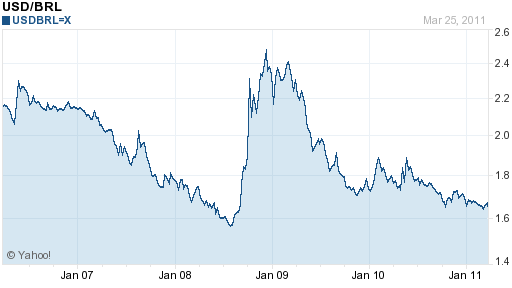

Over the last two years, the Brazilian Real has appreciated a whopping 37% against the US Dollar, second only to the South African Rand. It hasn’t been this strong since prior to the credit crisis, and it is rapidly closing in on a record high. If only Brazilian policymakers hadn’t made it a high priority to prevent that from happening.

The appreciation of the Real is being driven primarily by high interest rates, which in turn, are being driven by inflation. Brazilian prices are now rising at an annualized pace of 6%, which is well above the Bank of Brazil’s comfort zone. As a result, it has already raised rates several times in this cycle, including a 50 basis point hike at the beginning of this month. Its benchmark Selic rate now stands at a stratospheric 11.75%, which is higher than any other currency in the same tier.

Of course, the Bank of Brazil understands the implications of continuing to hike rates. With inflation as high as it is, however, it doesn’t really have much of a choice. Moreover, investors are betting on additional rate hikes, which means even wider interest rate differentials. When you also factor in a surprising lack of volatility surrounding the Real, it will certainly become an even more popular target currency for yield-hungry carry traders.

The government of Brazil, however, is doing everything in its power to repel this kind of speculation, lest it drive up the Real further and threaten the competitiveness of its export sector. In 2010, it tripled the tax rate on foreign investment in fixed income securities, to 6%. It increase scrutiny on local banks that have sought to borrow abroad. The national government has taken to doing more of its borrowing on the international market, and deposited the proceeds directly into its forex reserves, in order to mitigate the impact on the Real. The government is also contemplating punishing short-term investors by establishing a “lock-up” period for foreign capital.

And yet, Brazil finds itself in a quandary. While its trade balance has remained positive, its current account balance is now entrenched in deficit territory. Just like the US, it remaisn dependent on foreign investors to bridge this gap every month. Perennial budget deficits also mean the government can ill afford to alienate lenders. Finally, the government still wishes to attract legitimate foreign direct investment in infrastructure projects and portfolio investment in the stock market.

If Brazil is successful in limiting speculation – which is difficult, but not impossible given its determination – there is a chance that the Brazilian Real will hold steady. After all, Brazil saves less than it needs to invest, and inflation is high enough that there should be some natural downward pressure on the Real. On the other hand, if volatility remains low and speculators continue to find a way around the new capital controls (tempted by 11.75% short-term deposit rates), it will be difficult for the Central Bank to prevent its rise. It can only sit back, continue to hike rates, and pray that speculators soon lose interest.

Personally, I’m betting that the government of Brazil will achieve some measure of success, at least in the short-term. Of all the emerging-market countries engaged in the currency war, it seems to be the most resolute participant after China. At this point, short of fixing the Real to the Dollar, it has shown that it is willing to do whatever it takes to prevent speculators from winning.